Friday, November 11, 2005

Amy Smith M.I.T

http://www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,65276,00.html?tw=wn_story_related

An engineer who is uninterested in advancing technologies is, to put it mildly, a rarity. So rare, in fact, that the MacArthur Foundation awarded one such engineer $500,000.

Mechanical engineer Amy Smith, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology instructor, joined the MacArthur fellowship fold last week, receiving the so-called "genius award" and a colossal cash prize. Her award-winning feat? Using old technology in fresh ways to improve the lives of entire communities.

* Story Images

Click thumbnails for full-size image:

Mechanical engineer Amy Smith, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology instructor, joined the MacArthur fellowship fold last week.

* See also

* Robotic Fish Gather Data, Prize

* Science Women Get Cinematic Boost

* Fill 'er Up, With Microbes

* Ghana Gets a Fab Lab

* Discover more Net Culture

* Today's Top 5 Stories

* Biodiesel Keeps Home Fire Burning

* Machinima Marches Toward Amusing

* Should You Be in Pictures?

* Readers Respond to Bugging Out

* Curse's Beauty Is Skin Deep

* Wired News RSS Feeds

Special Partner Promotion

Find local technology jobs.

The MacArthur committee seeks dedication to original, creative pursuits that could affect the future. Smith's anonymous nominator probably didn't have a very tough sell. Smith has a stable of oldfangled technologies that she has reconfigured and applied to underdeveloped areas around the world. Her solutions -- including new grain-processing techniques, alternative cooking fuels and water-quality tests -- sound like answers to problems that should have been solved a century ago. To Smith, that's the point.

"Looking at things from a more basic level, you can come up with a more direct solution, and a lot of people go well, duh, that's really obvious!" Smith said. "But that's what you want: people saying it should have been done that way all along. It may sound small in theory, but it in practice, it can change entire economies."

Alternative fuels are one way to cultivate that change. Smith recently created some simple, effective methods to make charcoal from agricultural waste. The first method she developed after visiting Haiti was simple: First, the juice is squeezed from the widely grown sugar cane. Next, the remaining fibers, called bagasse, are sealed inside a 55-gallon drum. After the bagasse carbonizes from lack of oxygen, it is combined with a cassava-root porridge to bind it. Voilà: charcoal that can be used to cook, and manufactured as a business enterprise.

This new charcoal source can save lives in Haiti, where thousands die annually from massive flooding associated with the country's almost total deforestation. Until Smith began developing this alternative source of charcoal, Haitians had been forced to use trees as their sole source of cooking fuel.

Smith hopes other countries will benefit from local variations on her charcoal production method.

"We are adapting it for India, where the problem is the use of cow dung for cooking fuel," Smith said. "It's so abundant, but it also produces a lot of smoke. Breathing indoor cooking fumes is the No. 1 cause of children's death in the world. So if you can produce a cleaner-burning fuel, then you impact public health and the environment, as well."

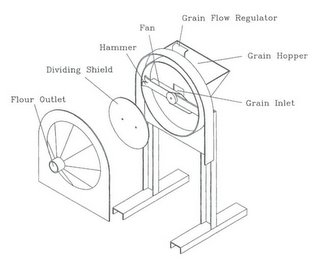

The next phase for Smith and her graduate-student team is to create a press to improve the briquette's density. She expects it to be simply designed and created with the local environs in mind -- something akin to the grain mill she also produced, which reduces the daily labor of grinding grain from four hours to just a few minutes.

Smith has said that a motorized hammer mill could grind grain into flour in a minute, but its flour screen is expensive and usually can't be built locally in rural areas. So two weeks ago she built a screenless mill prototype for one-fourth the cost of a conventional mill.

"A lot of people look at where technology is right now and start from there, instead of looking at the absolute functionality," Smith said. "If you go back to the most basic principals, you can eliminate complexity. The stuff I do is just very simple solutions to things, which is critical when you are developing applications for the third world."

Smith and her students have worked on an array of simple solutions to basic problems in the underdeveloped regions of the world: a water-testing kit that costs $20 instead of the usual $1,000, a phase-change incubator that tests for microorganisms in water supplies, peanut shellers and early-warning systems for flooding.

Shawn Frayne, one of Smith's former engineering students, likes a solution to a water problem that was making people ill in Honduras.

"A village in Honduras was getting over-chlorinated water because their chlorination tank did not have a way of controlling the flow of chlorine into the stream water," Frayne said. "So, Amy and her students solved the problem using the parts of a toilet tank. That's not a connection most people would make.

"The coolest thing is, she solved it on the spot. What's more, her solution not only works, but it is something that can easily be understood and repaired by people in that village, which means that it can be kept functioning long after Amy and her students have left," Frayne said.

Smith is now on a mission to bring her ideas to more people both inside and outside MIT. She hopes her affiliation with MIT will lend credence to the idea that innovating with the very basics of technology can effect major change in the world. Her half-million-dollar fellowship should help with that, too.

"I've always wanted to have funding to help the people with good ideas who I see and think, 'If only they had the resources, they could do this cool project,'" Smith said.

"I'd like to use a significant portion of the money to enable people who have the potential to make a significant impact in places like Haiti and India, the ability to just say, 'Hey, that sounds good, lets do it.'"

An engineer who is uninterested in advancing technologies is, to put it mildly, a rarity. So rare, in fact, that the MacArthur Foundation awarded one such engineer $500,000.

Mechanical engineer Amy Smith, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology instructor, joined the MacArthur fellowship fold last week, receiving the so-called "genius award" and a colossal cash prize. Her award-winning feat? Using old technology in fresh ways to improve the lives of entire communities.

* Story Images

Click thumbnails for full-size image:

Mechanical engineer Amy Smith, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology instructor, joined the MacArthur fellowship fold last week.

* See also

* Robotic Fish Gather Data, Prize

* Science Women Get Cinematic Boost

* Fill 'er Up, With Microbes

* Ghana Gets a Fab Lab

* Discover more Net Culture

* Today's Top 5 Stories

* Biodiesel Keeps Home Fire Burning

* Machinima Marches Toward Amusing

* Should You Be in Pictures?

* Readers Respond to Bugging Out

* Curse's Beauty Is Skin Deep

* Wired News RSS Feeds

Special Partner Promotion

Find local technology jobs.

The MacArthur committee seeks dedication to original, creative pursuits that could affect the future. Smith's anonymous nominator probably didn't have a very tough sell. Smith has a stable of oldfangled technologies that she has reconfigured and applied to underdeveloped areas around the world. Her solutions -- including new grain-processing techniques, alternative cooking fuels and water-quality tests -- sound like answers to problems that should have been solved a century ago. To Smith, that's the point.

"Looking at things from a more basic level, you can come up with a more direct solution, and a lot of people go well, duh, that's really obvious!" Smith said. "But that's what you want: people saying it should have been done that way all along. It may sound small in theory, but it in practice, it can change entire economies."

Alternative fuels are one way to cultivate that change. Smith recently created some simple, effective methods to make charcoal from agricultural waste. The first method she developed after visiting Haiti was simple: First, the juice is squeezed from the widely grown sugar cane. Next, the remaining fibers, called bagasse, are sealed inside a 55-gallon drum. After the bagasse carbonizes from lack of oxygen, it is combined with a cassava-root porridge to bind it. Voilà: charcoal that can be used to cook, and manufactured as a business enterprise.

This new charcoal source can save lives in Haiti, where thousands die annually from massive flooding associated with the country's almost total deforestation. Until Smith began developing this alternative source of charcoal, Haitians had been forced to use trees as their sole source of cooking fuel.

Smith hopes other countries will benefit from local variations on her charcoal production method.

"We are adapting it for India, where the problem is the use of cow dung for cooking fuel," Smith said. "It's so abundant, but it also produces a lot of smoke. Breathing indoor cooking fumes is the No. 1 cause of children's death in the world. So if you can produce a cleaner-burning fuel, then you impact public health and the environment, as well."

The next phase for Smith and her graduate-student team is to create a press to improve the briquette's density. She expects it to be simply designed and created with the local environs in mind -- something akin to the grain mill she also produced, which reduces the daily labor of grinding grain from four hours to just a few minutes.

Smith has said that a motorized hammer mill could grind grain into flour in a minute, but its flour screen is expensive and usually can't be built locally in rural areas. So two weeks ago she built a screenless mill prototype for one-fourth the cost of a conventional mill.

"A lot of people look at where technology is right now and start from there, instead of looking at the absolute functionality," Smith said. "If you go back to the most basic principals, you can eliminate complexity. The stuff I do is just very simple solutions to things, which is critical when you are developing applications for the third world."

Smith and her students have worked on an array of simple solutions to basic problems in the underdeveloped regions of the world: a water-testing kit that costs $20 instead of the usual $1,000, a phase-change incubator that tests for microorganisms in water supplies, peanut shellers and early-warning systems for flooding.

Shawn Frayne, one of Smith's former engineering students, likes a solution to a water problem that was making people ill in Honduras.

"A village in Honduras was getting over-chlorinated water because their chlorination tank did not have a way of controlling the flow of chlorine into the stream water," Frayne said. "So, Amy and her students solved the problem using the parts of a toilet tank. That's not a connection most people would make.

"The coolest thing is, she solved it on the spot. What's more, her solution not only works, but it is something that can easily be understood and repaired by people in that village, which means that it can be kept functioning long after Amy and her students have left," Frayne said.

Smith is now on a mission to bring her ideas to more people both inside and outside MIT. She hopes her affiliation with MIT will lend credence to the idea that innovating with the very basics of technology can effect major change in the world. Her half-million-dollar fellowship should help with that, too.

"I've always wanted to have funding to help the people with good ideas who I see and think, 'If only they had the resources, they could do this cool project,'" Smith said.

"I'd like to use a significant portion of the money to enable people who have the potential to make a significant impact in places like Haiti and India, the ability to just say, 'Hey, that sounds good, lets do it.'"

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

CASE STUDY OF "LIFE STRAW"

■ What is “LifeStraw”?

This is a water filter called “LifeStraw”.

“LifeStraw” is a portable water purification tool that cleanses surface water and makes it safe for human consumption. It is just 25 cm long and 29 mm in diameter and can be hung around the neck. “LifeStraw” requires no electrical power or spare parts. “LifeStraw” filters up to 700 litres of water and effectively removes most of the micro organisms responsible for causing waterborne diseases. The unit price is $2 under. And this is one of the winners of the 2005 INDEX design award in Denmark. (INDEX: It is the one of the world’s largest design and innovation awards. The first meeting was held in 2003)

■ What is designer’s WORK? What is social CONTRIBUTION of design?

This is one of the best examples to explain the social contribution of design.

That’s because it can save many valuable life and it is also very convenient to use and has a low unit price.

But it is also true that this kind of design makes me confused.

So I’d like to ask two groups of questions at the side of a professional industrial designer.

The first group of questions relates to the definition of design.

1. Can we say this is a designer’s work? In other words, what is a designer’s work and what is not a designer’s work?

2. What is the differentia between designer and engineer? In other words, Can’t engineers make “life straw”? Why is it made by designer?

3. In this respect, what should designers learn in school? And ultimately what is the competitive power of design or designer?

The second group of questions relates to the meaning of social contribution of design.

This is “iPod” by Apple Computer.

Compared to “LifeStraw”, can we speak iPod design is contributing to the human society?

“iPod” is beautiful and many people like this. Furthermore, it gives a huge amount of money to Apple Computer.

I change my question to this. Can we say the beauty of design contributes to the human society?

■ Conclusion

“LifeStraw” is not a money-making design. However human society needs this kind of design.

Although this kind of design doesn't make money or profit, it plays an important role of social contribution for people in the human society.

“iPod” is a different kind of design compared to “LifeStraw”. But “iPod” also contributes to the human society at a different view of design.

This is a water filter called “LifeStraw”.

“LifeStraw” is a portable water purification tool that cleanses surface water and makes it safe for human consumption. It is just 25 cm long and 29 mm in diameter and can be hung around the neck. “LifeStraw” requires no electrical power or spare parts. “LifeStraw” filters up to 700 litres of water and effectively removes most of the micro organisms responsible for causing waterborne diseases. The unit price is $2 under. And this is one of the winners of the 2005 INDEX design award in Denmark. (INDEX: It is the one of the world’s largest design and innovation awards. The first meeting was held in 2003)

■ What is designer’s WORK? What is social CONTRIBUTION of design?

This is one of the best examples to explain the social contribution of design.

That’s because it can save many valuable life and it is also very convenient to use and has a low unit price.

But it is also true that this kind of design makes me confused.

So I’d like to ask two groups of questions at the side of a professional industrial designer.

The first group of questions relates to the definition of design.

1. Can we say this is a designer’s work? In other words, what is a designer’s work and what is not a designer’s work?

2. What is the differentia between designer and engineer? In other words, Can’t engineers make “life straw”? Why is it made by designer?

3. In this respect, what should designers learn in school? And ultimately what is the competitive power of design or designer?

The second group of questions relates to the meaning of social contribution of design.

This is “iPod” by Apple Computer.

Compared to “LifeStraw”, can we speak iPod design is contributing to the human society?

“iPod” is beautiful and many people like this. Furthermore, it gives a huge amount of money to Apple Computer.

I change my question to this. Can we say the beauty of design contributes to the human society?

■ Conclusion

“LifeStraw” is not a money-making design. However human society needs this kind of design.

Although this kind of design doesn't make money or profit, it plays an important role of social contribution for people in the human society.

“iPod” is a different kind of design compared to “LifeStraw”. But “iPod” also contributes to the human society at a different view of design.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Amy Smith M.I.T

Amy Smith MIT – International Development Initiative

Goal: “people saying it should have been done that way all along. It may sound small in theory, but in practice, it can change entire economies.”

Model: not to design “new” products, but to apply new technologies to old products, on a case by case basis.

Haiti- massive flooding due partly to the mass deforestation of the island, Haitians who had originally relied upon trees for cooking fuel, now rely on her new form of charcoal based on the abundant sugar cane

Botswana – daily routine of grinding grain for food, labor and time have been reduced by the motorized hammer mill. An adaptation of existing product, this mill does not require a screen (which is where a majority of the life-cost per mill) a patent-less design in which she encourages patent infringement.

Strategy of Influence –

humanitarian – 1988 peacecorps

researcher – research and design-- 1996-funded by grants at MIT

leader - MIT – International Development Initiative

Goal: “people saying it should have been done that way all along. It may sound small in theory, but in practice, it can change entire economies.”

Model: not to design “new” products, but to apply new technologies to old products, on a case by case basis.

Haiti- massive flooding due partly to the mass deforestation of the island, Haitians who had originally relied upon trees for cooking fuel, now rely on her new form of charcoal based on the abundant sugar cane

Botswana – daily routine of grinding grain for food, labor and time have been reduced by the motorized hammer mill. An adaptation of existing product, this mill does not require a screen (which is where a majority of the life-cost per mill) a patent-less design in which she encourages patent infringement.

Strategy of Influence –

humanitarian – 1988 peacecorps

researcher – research and design-- 1996-funded by grants at MIT

leader - MIT – International Development Initiative

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

LIFE STRAW

http://www.index2005.dk/Members/dafude/bodyObject#

Designed in: Netherlands, Denmark, Israel

Problem:

Getting clean water to people in developing countries. The world’s greatest killer is diarrhoeal diseases from bacteria like typhoid, cholera, E. coli, salmonella etc.

Solution:

With LifeStrawTM, which lasts for one person's annual needs of clean water, nobody needs to die from these diseases. This design is made with special emphasis on avoiding any moving parts, to disregard spare parts, and to avoid the use of electricity, which does not exist in many areas in the Third World.

But as force is needed to implement the filtering, LifeStrawTM uses the natural source of suckling that even babies are able to perform.

The LifeStrawTM is produced at a price that people in the business find hard to believe, but it is essential to be able to present an affordable price to the consumer in the Third World. When fully used in the Third World this will indeed be a lifesaver.

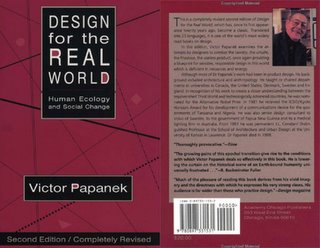

Victor Papanek

1999 Victor Papanek (1925-1998)

At its annual conference in Chicago, Illinois, IDSA posthumously honored Professor. Papanek for his 35 years of contributions to the design profession. As a member of design societies throughout the world, he transcended national and cultural barriers, and his books have been translated into many languages. His primary concern was using appropriate design for third-world countries.

Designer, anthropologist, writer, and teacher Papanek was born in Vienna, Austria and arrived in the US in 1932. He graduated in 1948 in architecture and industrial design from the Cooper Union, studied at M.I.T. and under Frank Lloyd Wright. He opened his own consulting office in 1953.

He became Dean of the School of Design at the California Institute of the Arts, and in early 1970s became Chairman of Design at the Kansas City (MO) Art Institute. He wrote a number of design-related books, including Design for the Real World, (1972), Nomadic Furniture (1973), Nomadic Furniture 2, (1974), How Things Don't Work, (1977), Design For Human Scale (1983) and Viewing the World Whole (1983). From 1981, Professor Papanek taught architecture and design at the University of Kansas.

.........................................................

Book Review by Raymond Jepson

http://www.914.qc.ca/monde.html

Design for the Real World by Victor Papenak

Design for the Real World is a watershed of liberal social and design thought. This should not discourage the conservative reader however as this book offers a fresh perspective on the design proffesion despite its age. It was written in 1970 by Victor Papanek, a former Purdue University professor of design, and accomplished designer in his own right. Victor Papanek was active in designing for non-profit organizations that help the under privlaged of the world. These two factors, teaching and designing for the masses permeates his book.

Victor Papanek's writting style is fluid and easy to read, even for someone not versed in the language of designers. Having said this, he does use the term "a priori" quite often, in my opinion more often than should be used, this is more an annoyance than a problem. Moreover, Papanek, I believe repeats his ideals too often. This factor makes the book at times tedious to read. He also provides at times too many examples. Where one or two examples would provide a clear understanding of some of his concepts, he adds two more. Once again, making the reading tedious. I prefer a book more to the point, although his examples are often entertaining, or poignant.

The content of the book is very provocative. To begin with is Papanek's perception of what design is, and the role of the designer. He defines design as being everywhere in people's lives, and rightly so. Moreover, he says "...design is an attempt to impose meaningful order." Papanek then goes into detail defining six areas of a design as follows: use, need, telesis, association, aesthetic, and method. Use is whether the design functions properly. Continuing with need, "Most recent design has satisfied only evanscent wants and desires....", Papanek says. Moreover, that these wants are used to sell useless, but profitable products. Utilization of natural processes is telesis. Association is the use of conditioned response of the user, such as cultural norms. Aesthetic equals producing a shape that moves us. Finally method, which is the interaction of tools, materials, and production process which forms a product. Papanek goes onto criticize products for being designed more for aesthetics than use, I think injustly. He says that clocks shouldn't be streamlined, since they don't usually move. He is being too critical of the role of the designer in this aspect, as the public does not always appreciate an honest use of materials, as is suggested by Papanek. Having said this, he does continually point out the material society that was and is still being formed. Papanek is critical of this material society as it tends to waste precious resources, pollute the enviroment, and have little if any constructive return to the society that produces them.

The role of the designer then is to utilize the aformentioned design principals, but Papanek believes the designer of today is using them in an immoral fashion. Papanek calls for a new social awareness of designers. Moreover Papanek shows that the designer can play a key role in the developement of the human race. The responsibility of the designer according to Papanek goes beyond sales, and marketing to a moral and social plane. The designer is responsible for the whole of built, human enviroment, and is therefore responsible for all enviromental mistakes. As such, the designer today is only concerned with a small portion of the local, country, and global design problems. The designer today is secluded in his upper middle class society, away from the vast majority of society. As such, Papanek suggests that every designer give 1/10th of their time to the 3/4 of human society with vital and unserved needs. This means giving time to designing products for these people, but moreover, teaching them. Papanek presents the idea of training designers in foreign and design-needy lands, so they can become design-independent. Papanek suggests a bold, yet very necessary developement of the designer as the the dicotomy of rich and poor grows greater seemingly daily.

Next, Papanek analyzes western society that breeds these decadent designers. In modern products he observes aspects such as designed obsolescence, where a product is designed, or styled in a way to force the consumer to buy a replacement in a rather short period of time. Moreover, the products designers are put in charge of designing have become adult toys rather than necessary tools of society. The role of the designer has been belittled to being no more than a marketing tool in itself, Papanek claims. Papanek suggests that designers take a more active role in product development. He suggests that more design for the poor must be established to help bring up their living standards. Also that the designer act as a consumer advocate inside companies, so that the product becomes as cost efficient, necessary and dependable as possible. Papanek provides vivid examples to support his views on the designers role in society, and also his opinions on the questionable products of his day. For example, he brings up some slide projectors by the Kodak company as examples of both good and bad design. The US version of the Kodak projector has 12 different models in their line up, none of which take plug-in upgrades, sticking the consumer with their choice. Kodak of Germany also produces a projector on the same basic parts, but only one. The German projector costs less, and has the ability to be upgraded with plug-in attachments, so the consumer can get the options they want. Moreover, the German version has safer wiring, and performs better than the American version. I believe this is an outrage of modern corporate thinking. The consequences of this kind of market policy is waste of raw materials, frustrated consumers, the increasing reliance on credit by consumers, and hazardous products. This aspect of Papanek's book was hardest felt, I believe, and has the deepest impact on the everyday life of consumer's which we all are.

Lastly, Papanek offers a surprising new thinking of education. The first part of Papanek's plan for the education of the designer is to teach them more than design. In Papanek's Purdue University industrial design program, he encouraged students from other fields to get a design graduate degree. Moreover, he promotes psychology classes and overall a more well rounded education than just drawing etc. The biggest difficulty Papanek has found in students dealing with design problems however, is their inability to be creative. He discusses in some length various blocks to creativity, such as perceptual blacks, the physical limitations of the designer, cultural blocks, those imposed by the culture in which the designer lives, associational blocks, the inhibitions caused by pyschological associations of objects, or situations, and emotional blocks, such as the fear of failure. Most of these blocks he claims are the result of the society surrounding the designer, therefore the designers education must break these learned blocks to creativity. The curriculum would be adjusted for this, in that the students would be taught by giving them situations outside their normal enviroment, this way not allowing the blocks to creativity to continue to apply.

In conclusion, I highly recomend this book to anyone with an interest in design, or society in whole. The book gives vivid insights to a all to rarely discussed aspect of modern society, which is partly the place of design, but moreover how resources should be distributed within society. It is a powerful book.