Victor Papanek

1999 Victor Papanek (1925-1998)

At its annual conference in Chicago, Illinois, IDSA posthumously honored Professor. Papanek for his 35 years of contributions to the design profession. As a member of design societies throughout the world, he transcended national and cultural barriers, and his books have been translated into many languages. His primary concern was using appropriate design for third-world countries.

Designer, anthropologist, writer, and teacher Papanek was born in Vienna, Austria and arrived in the US in 1932. He graduated in 1948 in architecture and industrial design from the Cooper Union, studied at M.I.T. and under Frank Lloyd Wright. He opened his own consulting office in 1953.

He became Dean of the School of Design at the California Institute of the Arts, and in early 1970s became Chairman of Design at the Kansas City (MO) Art Institute. He wrote a number of design-related books, including Design for the Real World, (1972), Nomadic Furniture (1973), Nomadic Furniture 2, (1974), How Things Don't Work, (1977), Design For Human Scale (1983) and Viewing the World Whole (1983). From 1981, Professor Papanek taught architecture and design at the University of Kansas.

.........................................................

Book Review by Raymond Jepson

http://www.914.qc.ca/monde.html

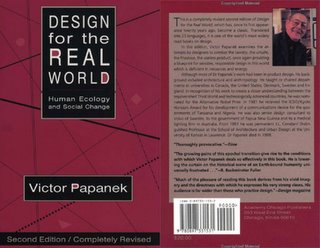

Design for the Real World by Victor Papenak

Design for the Real World is a watershed of liberal social and design thought. This should not discourage the conservative reader however as this book offers a fresh perspective on the design proffesion despite its age. It was written in 1970 by Victor Papanek, a former Purdue University professor of design, and accomplished designer in his own right. Victor Papanek was active in designing for non-profit organizations that help the under privlaged of the world. These two factors, teaching and designing for the masses permeates his book.

Victor Papanek's writting style is fluid and easy to read, even for someone not versed in the language of designers. Having said this, he does use the term "a priori" quite often, in my opinion more often than should be used, this is more an annoyance than a problem. Moreover, Papanek, I believe repeats his ideals too often. This factor makes the book at times tedious to read. He also provides at times too many examples. Where one or two examples would provide a clear understanding of some of his concepts, he adds two more. Once again, making the reading tedious. I prefer a book more to the point, although his examples are often entertaining, or poignant.

The content of the book is very provocative. To begin with is Papanek's perception of what design is, and the role of the designer. He defines design as being everywhere in people's lives, and rightly so. Moreover, he says "...design is an attempt to impose meaningful order." Papanek then goes into detail defining six areas of a design as follows: use, need, telesis, association, aesthetic, and method. Use is whether the design functions properly. Continuing with need, "Most recent design has satisfied only evanscent wants and desires....", Papanek says. Moreover, that these wants are used to sell useless, but profitable products. Utilization of natural processes is telesis. Association is the use of conditioned response of the user, such as cultural norms. Aesthetic equals producing a shape that moves us. Finally method, which is the interaction of tools, materials, and production process which forms a product. Papanek goes onto criticize products for being designed more for aesthetics than use, I think injustly. He says that clocks shouldn't be streamlined, since they don't usually move. He is being too critical of the role of the designer in this aspect, as the public does not always appreciate an honest use of materials, as is suggested by Papanek. Having said this, he does continually point out the material society that was and is still being formed. Papanek is critical of this material society as it tends to waste precious resources, pollute the enviroment, and have little if any constructive return to the society that produces them.

The role of the designer then is to utilize the aformentioned design principals, but Papanek believes the designer of today is using them in an immoral fashion. Papanek calls for a new social awareness of designers. Moreover Papanek shows that the designer can play a key role in the developement of the human race. The responsibility of the designer according to Papanek goes beyond sales, and marketing to a moral and social plane. The designer is responsible for the whole of built, human enviroment, and is therefore responsible for all enviromental mistakes. As such, the designer today is only concerned with a small portion of the local, country, and global design problems. The designer today is secluded in his upper middle class society, away from the vast majority of society. As such, Papanek suggests that every designer give 1/10th of their time to the 3/4 of human society with vital and unserved needs. This means giving time to designing products for these people, but moreover, teaching them. Papanek presents the idea of training designers in foreign and design-needy lands, so they can become design-independent. Papanek suggests a bold, yet very necessary developement of the designer as the the dicotomy of rich and poor grows greater seemingly daily.

Next, Papanek analyzes western society that breeds these decadent designers. In modern products he observes aspects such as designed obsolescence, where a product is designed, or styled in a way to force the consumer to buy a replacement in a rather short period of time. Moreover, the products designers are put in charge of designing have become adult toys rather than necessary tools of society. The role of the designer has been belittled to being no more than a marketing tool in itself, Papanek claims. Papanek suggests that designers take a more active role in product development. He suggests that more design for the poor must be established to help bring up their living standards. Also that the designer act as a consumer advocate inside companies, so that the product becomes as cost efficient, necessary and dependable as possible. Papanek provides vivid examples to support his views on the designers role in society, and also his opinions on the questionable products of his day. For example, he brings up some slide projectors by the Kodak company as examples of both good and bad design. The US version of the Kodak projector has 12 different models in their line up, none of which take plug-in upgrades, sticking the consumer with their choice. Kodak of Germany also produces a projector on the same basic parts, but only one. The German projector costs less, and has the ability to be upgraded with plug-in attachments, so the consumer can get the options they want. Moreover, the German version has safer wiring, and performs better than the American version. I believe this is an outrage of modern corporate thinking. The consequences of this kind of market policy is waste of raw materials, frustrated consumers, the increasing reliance on credit by consumers, and hazardous products. This aspect of Papanek's book was hardest felt, I believe, and has the deepest impact on the everyday life of consumer's which we all are.

Lastly, Papanek offers a surprising new thinking of education. The first part of Papanek's plan for the education of the designer is to teach them more than design. In Papanek's Purdue University industrial design program, he encouraged students from other fields to get a design graduate degree. Moreover, he promotes psychology classes and overall a more well rounded education than just drawing etc. The biggest difficulty Papanek has found in students dealing with design problems however, is their inability to be creative. He discusses in some length various blocks to creativity, such as perceptual blacks, the physical limitations of the designer, cultural blocks, those imposed by the culture in which the designer lives, associational blocks, the inhibitions caused by pyschological associations of objects, or situations, and emotional blocks, such as the fear of failure. Most of these blocks he claims are the result of the society surrounding the designer, therefore the designers education must break these learned blocks to creativity. The curriculum would be adjusted for this, in that the students would be taught by giving them situations outside their normal enviroment, this way not allowing the blocks to creativity to continue to apply.

In conclusion, I highly recomend this book to anyone with an interest in design, or society in whole. The book gives vivid insights to a all to rarely discussed aspect of modern society, which is partly the place of design, but moreover how resources should be distributed within society. It is a powerful book.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home